Two men were killed instantly. One man was buried up to his hips in liquid setting concrete. He was pinned by debris and they could not get him out. They had two hours before the concrete set. He was alive and he was screaming. They tried pouring sugar in the concrete to stop it setting. They found out afterwards there would have been no hope because the man’s legs had been virtually severed in the accident and the only reason he wasn’t dead was that the blood wasn’t able to escape because of the concrete around him. (Source)

If you're interested, Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen have a recent album inspired by the stories of the migrant workers on the scheme. The song "The Sun Will Shine In" particularly reminds me of this place: I wake up in darkness, I work all day in darkness, I go to sleep in darkness . . .

Let us lament for Jindabyne, it is going to be drowned,

Let us shed tears, as many as the occasion warrants;

The Snowy, the Thredbo and the Eucumbene engulf it

Combining their copious torrents.

Over almost thirty stanzas, Stewart lists “all Jindabyne has to offer” in less than complimentary tones, concluding half-way through the poem that “Nothing, except the hotel, was built for permanence”, and:

Many a time thus viewing the total township

And thinking how soon it was all to be buried in water

Like drowned Atlantis and never be heard of again

I have thought: the sooner the better

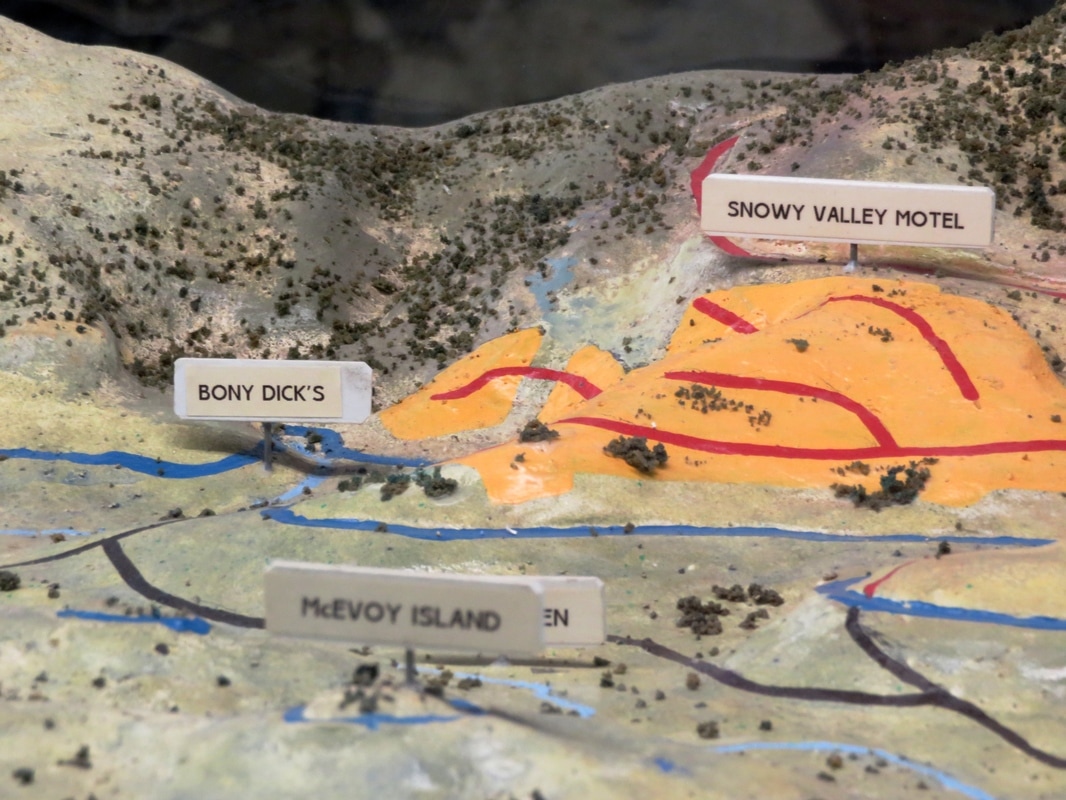

Worrying the issue over, Stewart name-checks the people and their properties soon to be submerged (note the European names): Hans at the Kookaburra Cafe, Rankin’s and Jindabyne Motors, Leo A. Hore at the pub, E. Kluger and “his famous salami sausages”. But soon enough, he remembers that all these people will be re-homed in New Jindabyne.

What the poem leaves out - as does much of the writing about the scheme - is the loss of older sites, places important to the Ngarigo and other Aboriginal groups. Stewart’s view of Indigenous people is of:

The shy dark shadowy aboriginal race

Always like creatures in water, who left one word

And vanished without a trace . . .

It’s a summary that suggests the disappearance of Aboriginal people is complete (it isn't) and that such a disappearance is a sad inevitability (rather than a concerted regime of violence by colonisers). Stewart doesn't talk about Aboriginal cultures, stories and places lost beneath the water. There were no surveys of such sites done before construction, but had there been the surveyors might have listed places similar to those found elsewhere throughout the high country, the Monaro and the Snowy valley: camp, shelter, ceremonial and stone tool manufacture sites, middens, scarred trees (either carved to mark the burial places of important people, or scarred in the removal of bark to make shelters, canoes, shields, baskets), or other things not so bounded by a specific physical location - a landscape or a particular view, part of a songline, specific geological features, plants or animals. Stewart contends that Aboriginal people left behind only a single word - presumably the word “Jindabyne”? - so whereas he and his implied audience are able to get a bit nostalgic for the homes and cultural hubs of ‘modern’ Australia (houses, pubs, shops, churches), the Indigenous equivalents (art, artefacts, sacred sites, names and stories) remain unlamented.

The moon took the water from the ocean, and travelled to the mountains to the north. The platypus followed, and busted the moon’s waterbags when the moon fell asleep in the mountains. The water gushed out and made the Snowy River and all its children..

RSS Feed

RSS Feed