NB: This post contains photographs of a dead animals and bones.

Charlie Rugman, Boloco Cemetery, Beloka |

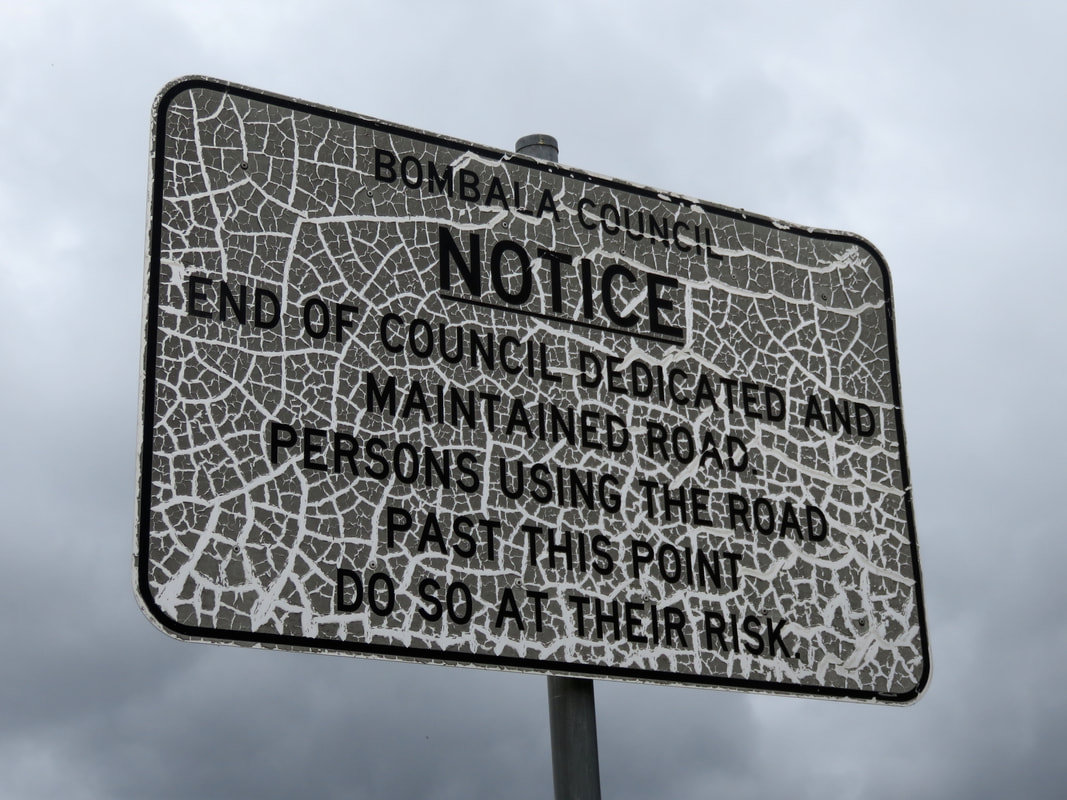

The roads took us through grasslands choked with lamb’s ear and thistle and hoarhound, past neat, abandoned farm houses. Perhaps the successful graziers are those who have land elsewhere, somewhere the grass can catch a coastal rainstorm and cattle can put some flesh on their bones before market. Somewhere the local council hasn’t given up on spraying the worst of the weeds. Somewhere the wild dogs don’t terrorise the ewes into miscarrying, or pick off the calves with the tiredest mothers.

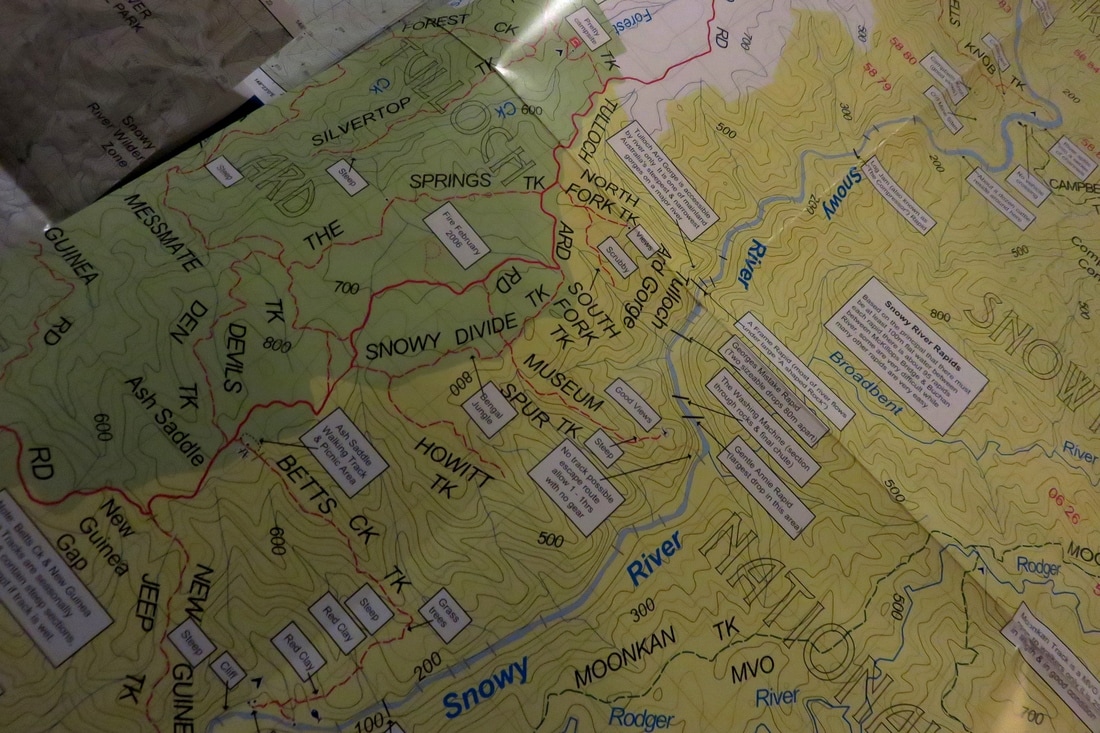

It consists of a drop of perhaps twelve metres over a distance of about 200 metres, but it is not an ordinary rapid so much as a massive and intricate piece of rock sculpture. The rock is a hard, dense and mostly fine-grained granite, with many inclusions (xenoliths) of a dark rock that had been shattered by the molten granite as it was squeezed into place below the surface of the earth. This granite has a massive jointing system, planes of weakness set at right angles, three or four metres apart. The rock has not weathered into the usual rounded boulders, but into great cubes, although the edges have been rounded and under-cut. The result is a series of almost horizontal rock pavements, almost vertical rock walls, and deep slots. At one point, the entire river disappears into one of the slots, where it can be heard and sometimes glimpsed moving with great force some four metres or so below, eventually to emerge from fissures and slots lower down. There is no real ‘bridge’, and it is quite difficult to clamber across because of the changes in level and sheer faces, but the river itself is well out of sight.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed