Several months ago, the Dark Mountain Project put out a call for submissions for their fourteenth issue:

In a restless, globalised culture which dictates that all places be the same and none of us loyal to a heartland, it is sometimes hard to make ourselves at home on Earth. As Martin Shaw writes, to become ‘of a place’ is to trade ‘endless possibility for something specific’. Some of us commit to deepening our investigations of one place, digging in and giving voice to the inhabitants (human and non-human) of the neighbourhoods in which we live. . . For the fourteenth issue we seek work which challenges borders and celebrates transgressions. . .

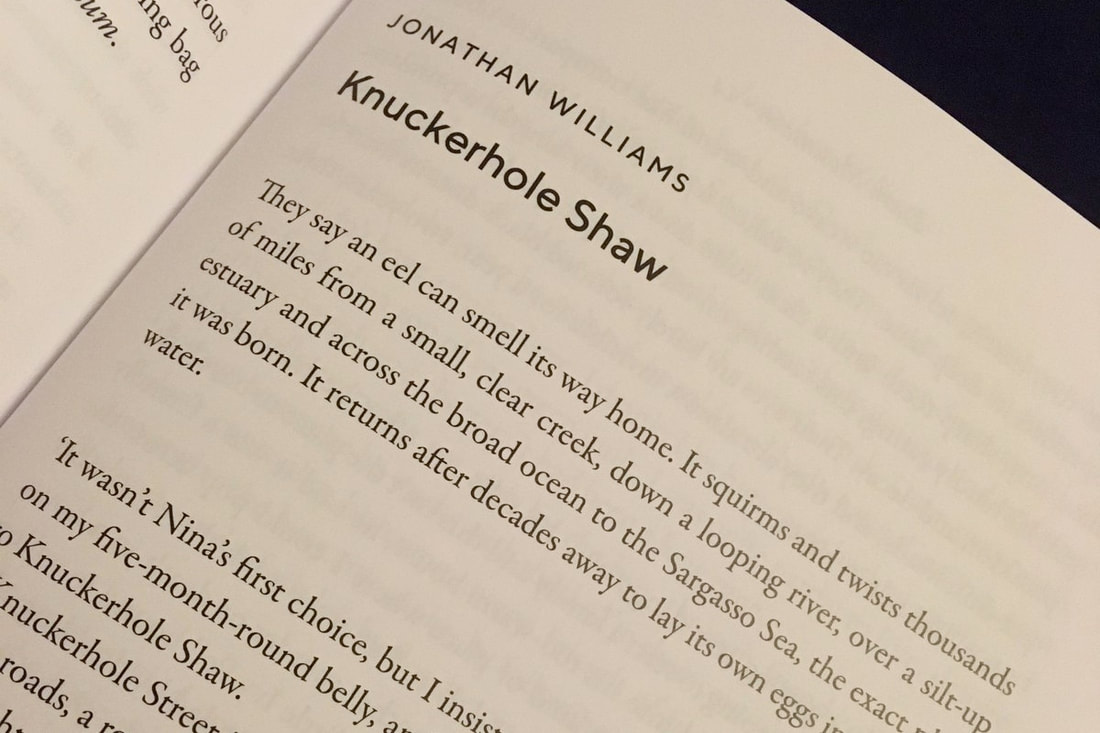

I first drafted the story in late 2014 and submitted it to another publication in 2015 - it was rejected, but with a couple of lines of helpful feedback. Some friends also read through it and gave me pointers (thanks Emily and Dan). Over the next few years, I revisited the piece occasionally, filling out the story and directing it towards a more satisfying conclusion while striving to keep the potential for ambiguity. The Dark Mountain submission deadline prompted me to give it a good polish and call it finished a second time.

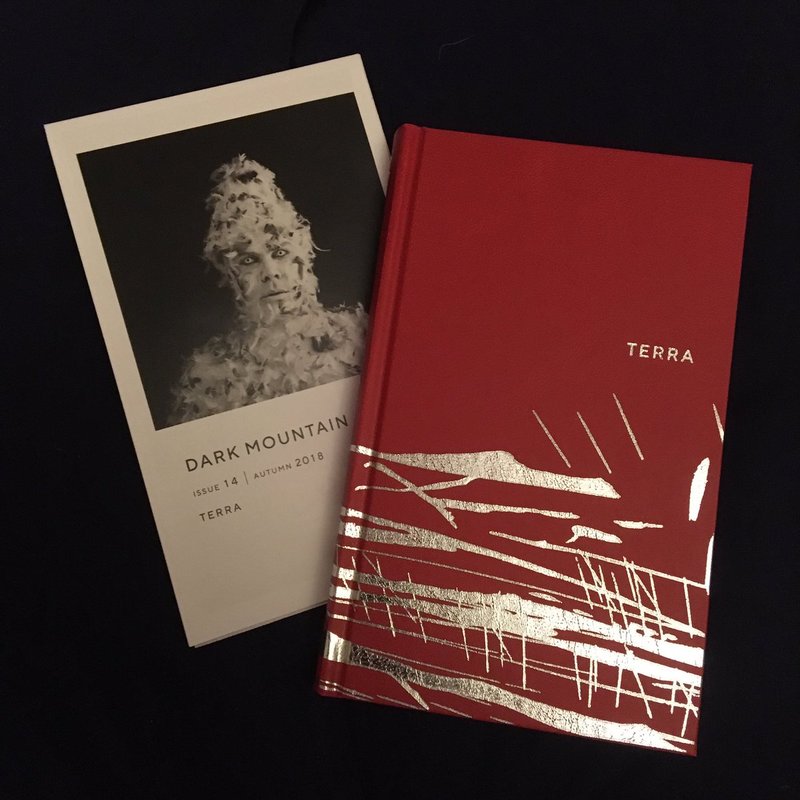

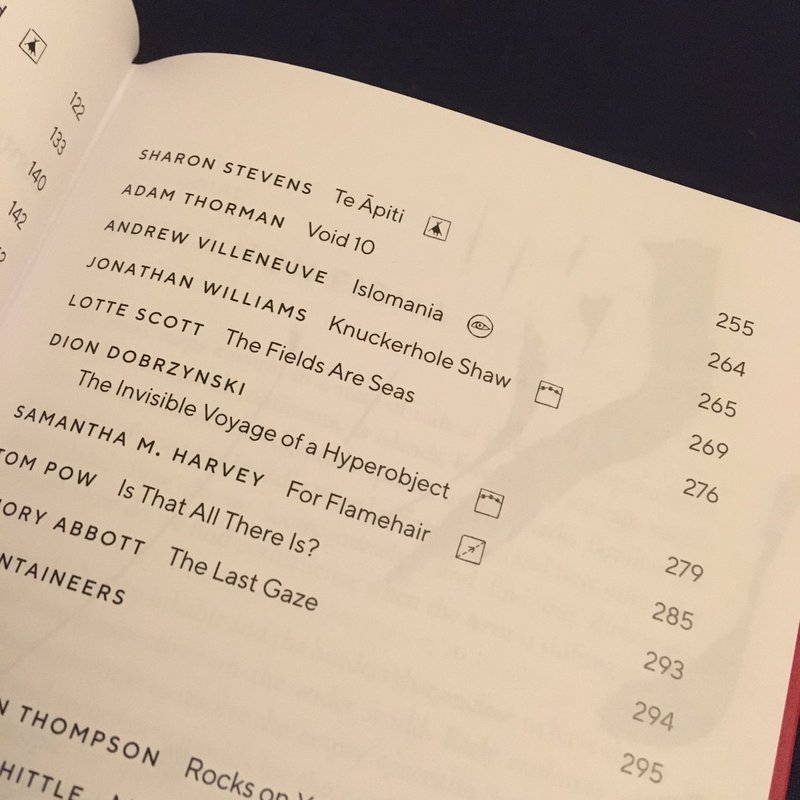

And the final product is just gorgeous - a beautiful book that I’m really proud to be part of. The written pieces (mainly non-fiction) are interspersed with visual art (mainly photography) and the sympathetic collation guides the reader deftly across continents, oceans and themes. I'm about half way through, and at almost 300 pages I think it will keep me going for a while as I dip in and out.

I’ll end with a short excerpt from my story, to tempt you into purchasing your own copy!

The archivist’s voice weaves a loose net. I try to slip through, thinking instead of what I will do tonight: of a bath in the big tub with the dragon feet; or food: two months to go, and boiled eggs and pies are grit between my teeth, but I must feed. ‘There was always a legend about marsh babies,’ she says, ‘of children found on the Levels wailing for food and shelter until a local family took them in.’ Her sentences tighten around me and I flinch, push the chair back and stand to rub the aching muscles of my back. He barely notices. ‘Of course, it’s more likely the children were born out of wedlock, perhaps even a product of sexual assault,’ she continues, and I start to walk the room, staring at the shelves. ‘The mothers or the girls’ families wanted to get rid of the babies without killing them outright. They might stand a chance, this way.’

He doesn’t believe the story. I feel his eyes on me, his annoyance at my slow, shuffling pace. But he is not quite dangerous, not yet. I smell his wet soil breath as he sighs. ‘Go and look around,’ he tells me. He smells good. I obey.

Two steps down through a broad arch, the museum is a long room, well lit and white-walled. Glass boxes hold single items: rusted, flaking metal tools and spalt, split timbers – isolated, their decay safely contained. Ash-grey lettering on the walls spells out their long-forgotten uses, but one I know on sight, stabbed through. Eelshear, it says. An iron instrument with three or four points, fastened to the end of a long pole, by means of which it is thrust into muddy ponds and ditches for the purpose of catching eels. Under that, an etching of the fork in use, along with a conservation note. European eel (Anguilla anguilla). IUCN Red List classification: Critically endangered.

It is never safe to live with a hunter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed