1. Wanderlust: A History of Walking

What’s it about? It does what it says on the tin. It starts with the physiology of walking, an investigation of why humans started walking, then wanders through time over diverse fields including philosophy, shopping, poetry, religion and spirituality, landscaping and gardens, tourism, geography, politics, novels, pop culture, law, feminism, public space and urban design. It moves between continents, too, though there’s a definite bias towards the northern hemisphere.

Why is it so good? Solnit highlights that is a history, not the history: she tries to acknowledge the book's limitations, omissions and biases. Rather than being a straight-up chronological history, it's more a series of lyrical essays. Academic analysis is interspersed with personal accounts of walks (taken solo or with friends) and occasional flights of imagination are thrown in. I like it because, like a good walk, it takes you to new places, and asks you to look at familiar things in a different light.

Any cons? I would like to hear more non-Western perspectives, and some of the chapters are a little thinner on ideas and research than others. Even those chapters, though, seem to open up the potential of walking and thinking about walking, rather than shutting it down with a definitive “this is how it is, because I am an expert and I say it is so”. Another con, which you can take as read in almost any contemporary writing about walking, are the instances of casual fatphobia and hand-wringing about “the obesity epidemic” - boring.

2. Map Addict: A Tale of Obsession, Fudge and the Ordnance Survey

What’s it about? Strictly speaking, as the title suggests, this is a book about maps rather than walking. But since this is my list, I have decided there is enough walking in there to qualify. This is a humorous non-fiction book - slightly in the vein of Bill Bryson, to give you an idea of tone. It is a bit of a whirlwind of subjects, but it pulls together to give a fun, biased and incomplete investigation of cartography, borders, land use and land access (including walking), politics and language. It’s set mainly, but not exclusively, in the British Isles - but it doesn’t claim to be anything other than very British.

Why is it so good? How can you not like someone who used to shoplift maps in their misspent youth? Parker is so obsessed with Ordnance Survey maps that I’m sure even the most map-phobic person couldn’t help but feel a spark of enthusiasm! He’s got a good eye for the off-beat (like visiting the most boring OS gridsquare), though many of the mainstays of mapping and walking are in there too (Wainwright, Phyllis Pearsall of the London A-Z fame, the Ramblers). Maps are a huge part of my experience of moving through and understanding the world, so it’s great to read something light-hearted while also learning a bit more about why the world of mapping (and, by extension, walking) is the way it is.

Any cons? Sometimes Parker’s exceptionally bouncy approach does make things pass in a bit of a whirl - you will find a more balanced, exceptionally researched but infinitely drier account of the OS in Rachel Hewitt’s Map of a Nation. Also a con in a list of books about walking is that there isn’t more walking it - though to be fair, Parker has written a book about walking and footpaths (The Wild Rover), it’s just that this one’s more fun.

3. The Ways of the Bushwalker: On Foot in Australia

What’s it about? A history of bushwalking, which Harper defines as walking in the bush for pleasure. This is an interesting companion book to Wanderlust, as it covers a few similar areas but with an Australian focus. There are discussions of politics, fashion, gender, four-wheel driving, ecology, aesthetics, literature and colonisation. Because it has a much narrower scope than Wanderlust, it is able to zoom in on more details and quirky bits of Australian history. It's something of a cultural history through the lens of walking.

Why is it so good? There are lots of histories and philosophical examinations of walking, but there’s hardly anything specific to Australia. This book opened my eyes to pieces of Australian history I’d known nothing about, and it prompted me to start thinking more deeply about the problematic concept of “wilderness” - specifically, how the kinds of ideas and ideals embedded in the National Park movement can be inherently, unconsciously racist and also used for explicitly anti-Indigenous Australian means (watch Noel Pearson’s speech for more on that). I also loved the chapter on people who aimed to experience the bush physically, almost erotically, especially through naked walking.

Any cons? While there are discussions of land rights, Harper argues her “walking in the bush for pleasure” definition means that bushwalking (a term coined in the 1920s) excludes the long history of Indigenous Australians walking in the bush. I think there could have been another chapter dedicated to Aboriginal history, e.g. walking Songlines (though research in that area has also been problematic).

4. Two Degrees West: A Walk Along England’s Meridian

What’s it about? Nick Crane (of BBC’s Coast fame) walks a straight line through England from Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland to the south coast near Swanage in Dorset. Of course, it’s not completely straight, but his aim is to veer no more than 1km each side of the prime meridian - not even for food and shelter. His other aim is to do it all on foot. (Spoilers: he achieves the former, and from memory there are only two exceptions to the latter - he crosses a reservoir by boat and some MOD land in military transport).

Why is it so good? This book is sometimes subtitled “An English journey”. I prefer the subtitle I’ve cited, but I can see why this one exists: in walking a straight line, rather than following established paths, natural landmarks, roads and so on, Crane is able to observe an almost randomly selected cross-section of English culture, people, landscapes, towns, agriculture and industry. It’s a cultural examination masquerading as travel writing. I like the inclusion of urban landscape and the bit where he sleeps in a culvert under a motorway.

Any cons? Crane documents his nervousness about trespassing, practicing his super-fast “pitch” in case anyone stops him. Nobody does. I wonder how anyone who wasn’t a moderately respectable-looking middle aged white man would have fared? I wonder if it would still be possible to do this walk almost 20 years later? I love the idea of this kind of walk (there are shades of Richard Long's art), but I wish there were more done by people who haven’t traditionally been allowed such freedom of movement.

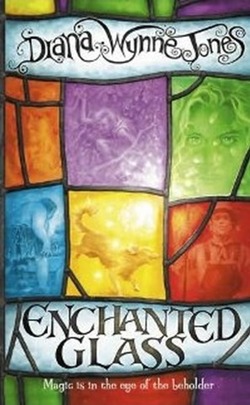

5. Enchanted Glass

What’s it about? This is a children’s fantasy book, about magic and family and many of the things you might expect from Diana Wynne Jones (she wrote Howl’s Moving Castle, which is one of my favourites of hers alongside The Homeward Bounders and The Spellcoats (from the Dalemark Quartet)). Enchanted Glass is about a young, orphaned boy (Aidan) and a featherbrained male academic who wind up living together in Melston House, a fictional house near the fictional town of Melston in England. The house comes with a “field of care” - like a parish surrounding a church, only one which must be magically maintained by the inheritor of the house. Oh, and Aidan is being pursued by a mysterious, hostile force...

Why is it so good? The field of care is tied very strongly to physical boundaries, which must be physically seen to, with obstacles removed. The magic here draws on the tradition of beating the bounds. I love this concept because it ties into a way of seeing and being in the world that I want to explore through reading and writing - the dual ideas that the landscape is a living entity that has a kind of ownership on the people living there and the idea of magic being done through physical movement. Plus, it’s a fun tale!

Any cons? If you’re after books that are only about walking, this isn’t one. Also, in terms of fiction, it would have been nice to have some more female characters. Oh, and, here’s a spoiler: I was disappointed when the main characters ended up being related by blood - it wasn’t necessary and gave off a "chosen families aren’t real families" vibe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed